The tale of an escaped convict who lived in the bush for 32 years with the Wathuroung aboriginal people before the settlement of Melbourne.

In 1803, when the transportation of British convicts to Australia is at its height. An attempt is made to start a settlement in Port Phillip Bay at modern day Sorrento. The mission is doomed to failure because of a lack of an adequate water supply, but before it relocates to Van Diemen’s Land and starts the settlement of Hobart Town, a handful of convicts escape their captivity by fleeing into the bush. Among them is a 6ft 5, 23 year old, former soldier named William Buckley. With the nearest sign of civilization at the time being the convict colony at Sydney, more than 850 kilometres away and with no maps or supplies the men are given up for dead.

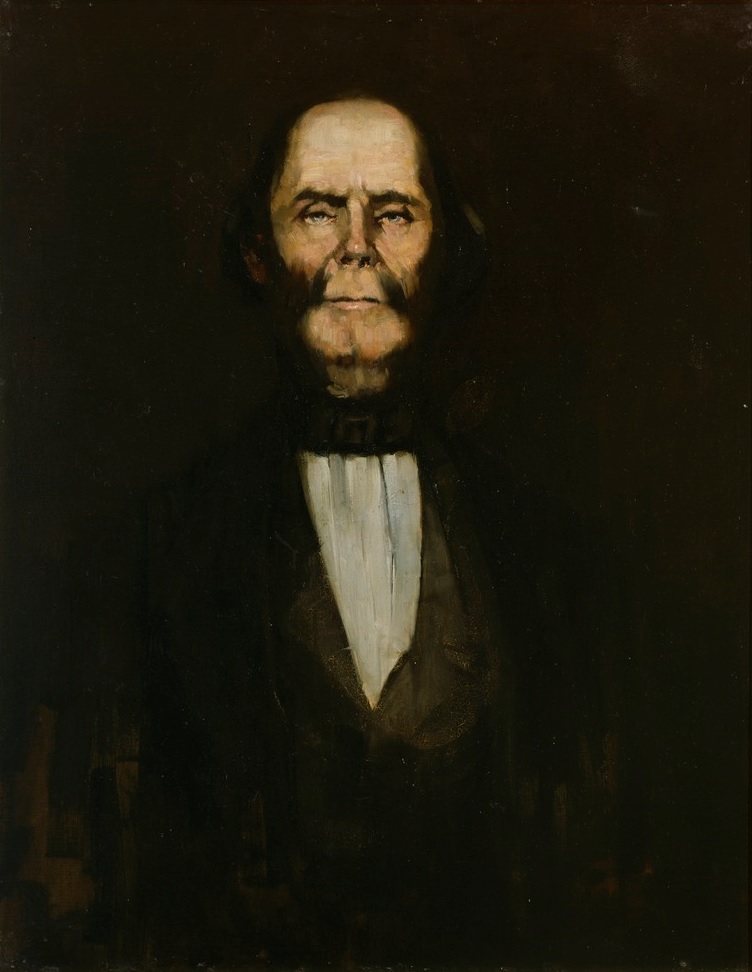

Later, when the settlement of Melbourne has just begun, and a basecamp for the settlement has been set up at Indented Head on the Bellarine Peninsula to await the return of supplies from Van Diemen’s Land, a stranger walks into the campsite. Whoever it is is a giant of a man. He has long white hair and a long white beard. He’s dressed in possum furs and carries two spears. It is William Buckley. He’s been away from civilization for so long he’s forgotten how to speak English.

This is 1835, he’s been living in the wild with the Wathaurong aboriginal people for 32 years

In researching this story I’m relying largely on the 1852 biography ghost written by John Morgan called The life and adventures of William Buckley : thirty-two years a wanderer amongst the aborigines of the then unexplored country round Port Phillip, now the province of Victoria. It is the longest and considered the most authoritative source of Buckley’s life. However, it differs in some key respects to some other much shorter, contemporary accounts of the time which I we will discuss at the appropriate time.. Others criticise Morgan’s account for over embellishing certain aspects of Buckley’s story, however, historians tend to agree that Morgan’s account, as it is written in Buckley’s own voice, is the most accurate account we have.

However, I will say it is impossible to know for sure the truth of all the events that occurred as we are reliant on the veracity of Buckley’s story and the integrity of Morgan to avoid using creative licence. Ultimately, I think it is up to the reader as to how much of the story they should take for fact. The account would certainly reads as controversial to modern eyes in some respects. Particularly in its representation of the constant warfare and violence between the aboriginal ‘tribes’. There are also a number of accounts of cannibalism detailed amongst them and certainly the way this is represented by Morgan is in a extremely patronising way as he clearly looks down on what he regards as the uncivilised nature of the aboriginal savages and comes across as racist to a modern reader.

William Buckley was born in 1780 in Macclesfield, Cheshire, England. He had two sisters and a brother and his parents were farmers. He was adopted by his mother’s father and at the age of 15 was apprenticed as a bricklayer to a Mr Robert Wyatt. Buckley clearly didn’t enjoy this lifestyle because at the age of 19 he ran away and joined the Cheshire Militia. He describes receiving a bounty of ten guineas for this and remembers thinking this amount of money would last him forever.

After a year, his money had exhausted and he volunteered in the King’s Own Regiment of Foot at Horsham in the south of England a long way from his native Cheshire. After only 6 weeks here his unit was ordered to to embark for war in Holland where the Duke of York was in battle against the French Republic. Buckley’s regiment under the command of the Earl of Chatham suffered heavy losses in this battle and Buckley’s hand was severely injured although he doesn’t detail how this injury occurred.

On returning to England Buckley received another bounty for extended service. His officers had a good opinion of him because of his height, he was six foot five, and his good conduct. But, soon afterwards he fell in with a bad crowd he had met in the regiment and was arrested for receiving false goods.

Buckley always maintained his innocence in this affair saying that a woman asked him to collect some items for her and then he was arrested by authorities for receiving stolen goods. He was found guilty in court and after this sentence he never heard from his family again.

As a prisoner he initially worked on fortifications being built at Woolwich, but as a mechanic he was identified as possibly being useful to a new penal colony that was to be set up at Port Phillip in what was then New South Wales.

Buckley saw this as an excellent opportunity to redeem his sullied name and so he embraced being sent for transportation to the other side of the world. This is noteworthy when you consider the hardships that often went hand in hand with a marine trek to the Antipodes.

A journey from England to what was called New Holland at the time took the best part of a year to complete and trips were arduous affairs that often involved the deaths of upwards of 10% of those who embarked.

This is not to mention the exceptional remoteness of the colony. The convicts were expected to build infrastructure when they arrived in a complete wilderness. This says a lot about Buckley’s character that he was willing to embrace his transportation in order to redeem himself.

On top of this, prisoners were often treated cruelly in a time when severe punishments were the rule. Lieutenant Colonel David Collins was chosen to lead the expedition and to be the governor of what was to be the first settlement in modern day Victoria. They set sail in two ships, the Calcutta and the Ocean.Buckley was treated well on the journey and spent most of the time helping out the crew.

When they arrived the ships anchored 2 miles within the heads at a place Collins named Sullivan Bay. This site was chosen as a penal settlement because it was over 600 miles from Sydney which meant escape would have been practically futile.

The marines and convicts landed and encamped and Buckley mentions how, while most of the convicts had to camp inside a line of sentinels, he and the other mechanics were permitted to camp outside it and were set to work on the first buildings of the settlement.

Life, though, was tough at the new settlement. There was no access to a reliable fresh water supply and the soil proved poor for growing crops. So, after 3 months of roughing it Buckley and 3 others decided to make an escape from their bondage.

Buckley in 1852 freely admitted to the madness of this plan, as it involved walking to Sydney 600 miles to the north.

With no maps though and no idea which direction Sydney lay in, the attempt was utterly pointless and perhaps speaks of the desperation he felt at the time, especially considering the settlement was attempting to survive on brackish seawater.

Buckley and his 3 companions had been entrusted with a gun to shoot kangaroo in the area they were working in.

One dark night they absconded with the gun, an iron kettle and as many supplies as they could take. They were spotted however, by a sentinel who shot at them, taking down one of Buckley’s companions. He never found out if this man survived as he never heard from him again.

In fear for their lives the 3 remaining men ran for 3 or 4 hours before stopping for a break. Not long after renewing their march they came to a river now known as Balcombe Creek in Mouth Martha.

At daylight they began to renew their trek when they encountered a party of natives. This was the first encounter Buckley had with any of the natives that we know about. He says he fired the gun in order to scare them off and they ran into the bush.

Buckley crossed first to test the depth and then helped the others across and went back for their clothes.

That night they reached to about 20 miles from the modern city of Melbourne and rested there until the morning when moved on again until they crossed the Yarra River a few hours later.

Do you enjoy this content? Would you like to see more of it? Please help me reach my goal of publishing a book on Mr Cruel by making a one-time donation to help me cover the many costs I have incurred in carrying out this research. These costs have included subscription costs to a host of research tools and databases and costs associated with running this website and the associated podcast.

Make a one-time donation

Do you enjoy this content? Would you like to see more of it? Please help me reach my goal of publishing a book on Mr Cruel by making a monthly donation to help me cover the many costs I have incurred in carrying out this research. These costs have included subscription costs to a host of research tools and databases and costs associated with running this website and the associated podcast.

Make a monthly donation

Do you enjoy this content? Would you like to see more of it? Please help me reach my goal of publishing a book on Mr Cruel by making a yearly donation to help me cover the many costs I have incurred in carrying out this research. These costs have included subscription costs to a host of research tools and databases and costs associated with running this website and the associated podcast.

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is greatly appreciated appreciated.

Melbourne Marvels

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

Melbourne Marvels

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

Melbourne Marvels

They crossed the river and continued their way up the Mornington Peninsula crossing the Yarra River the next day. After this, they headed away from the coast and travelled through vast plains until they reached the Yawang Hills (today knows as the You Yangs). Here they finished the last bit of bread and meat they had taken with them.

As they were incapable of finding any food Buckley told his friends they must return to the bay to find shellfish or they would die of starvation and they agreed so they returned to the coast after what Buckley called “a long and weary march.”

They were able to subsist off shellfish, travelling down the west coast of Port Phillip Bay through the areas of modern day Corio and Port Arlington. But, life was becoming a serious struggle. Water was hard to come by and the only thing they had to eat was shellfish and which caused the men to suffer from diarrhea.

By this stage the men had been gone for a few days. There were thirsty, tired, suffering from diarrhea and they had started seeing native huts dotted about the place.

The indigenous people who lived in the area at the time, known as the Wathaurong people, were a nomadic hunter-gatherer people much like the other Australian indigenous peoples. They would often build these temporary huts made from bark and tree branches and then they would abandon them or perhaps come back to them at a later date. So, these 3 European men were seeing these types of huts around the place, but they were not occupied.

Buckley and his companions must have felt great fear at the prospect of bumping into these tribes as they referred to them. The common early 19th century trope that was in the backs of their minds was that these were untamed savages who would eat them as soon as greet them, so it can be imagined that they were somewhat concerned about this inevitable meeting. But, apart from the meeting they had had on their second day from the settlement on the other side of the bay, in this area they were only encountering vacant huts.

The next day they reached an island the Wathaurong called Barwal, which is called Swan Island in modern parlance. Buckley mentions how they could reach the island during low tide. Even today if you look at Swan Island on Google Maps you’ll see that the island is separated from the mainland by a very narrow strait of water.

Melbourne sits on the Northern tip of a large bay, but the point of entry to the bay is a very narrow strait at the Southern end. The Calcutta had anchored just inside the Eastern head of the bay and so the 3 escapees had walked around the entire length of the bay from the eastern head to the western head a journey of well over a hundred and close to two hundred kilometres. From Swan Island which lies just inside the Western head of the bay they could actually see the Calcutta at anchor on the other side as the bay considerably narrows the closer to the Heads you get. So, these men were exhausted, dehydrated and hungry, and in their minds they were in danger of being captured and potentially eaten by roaming packs of savages.

Suddenly the prospect of returning to the settlement started to look appealing. Sure they might be punished, they might have their sentences lengthened, but at least they would have a roof over their heads and something to eat and drink, and didn’t have the threat of being cannibalised at any moment hanging over their heads.

Buckley relates what happened next:

“The perils we had already encountered damped the ardour of my companions, and it was anxiously wished by them that they could rejoin her (meaning the Calcutta), so we set about making signals, by lighting fires at night, and hoisting our shirts on trees and poles by day. At length a boat was seen to leave the ship and come in our direction, and although the dread of punishment was naturally great, yet the fear of starvation exceeded it, and they anxiously waited her arrival to deliver themselves up, indulging anticipations of being, after all the sufferings they had undergone, forgiven by the Governor. These expectations of relief were however delusive; when about half way across the bay, the boat returned, and all hope vanished. We remained in the same place, and living in the same way, six more days, signalizing all the time, but without success, so that my companions seeing no probable reply, gave themselves up to despair, and lamented bitterly their helpless situation.”

Buckley goes on to relate how at the end of the next day, his companions decided to retrace their steps round the bay and return to the settlement. He spells it out thus:

“To all their advice, and entreaties to accompany them, I turned a deaf ear, being determined to endure every kind of suffering rather than again surrender my liberty. After some time we separated, going in different directions. When I had parted from my companions, although I had preferred doing so, I was overwhelmed with the various feelings which oppressed me: it would be vain to attempt describing my sensations. I thought of the friends of my youth, the scenes of my boyhood, and early manhood, of the slavery of my punishment, of the liberty I had panted for, and which although now realized, after a fashion, made the heart sick, even at its enjoyment. I remember, I was here subjected to the most severe mental sufferings for several hours, and then pursued my solitary journey.”

Now you may be wondering at this point what Buckley was doing on the Western side of Port Phillip Bay considering he was trying to reach Sydney. The elder Buckley wonders this himself in 1853 and reflects at how futile the quest of his younger self was.

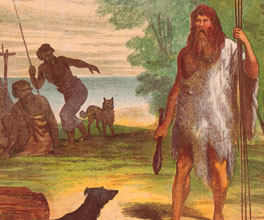

On the first day of his solitary wanderings one of Buckley’s greatest fears was realised in that he encountered a group of about 100 aborigines in and near some huts made of bark and branches and some of them made towards him. Fearing for his life, Buckley jumped into a river with his clothes on whilst carrying his firestick. Luckily the natives didn’t follow him into the river, but in quickly jumping into it all his clothes were drenched and he had no longer any means by which to start a fire to keep warm. He had to sleep on the bank of the river that night in wet clothes in early Spring, which must have been close to unbearable.

The next day he returned to the beach making sure he wasn’t seen by the natives. As it was low tide, he found lots of abalone which the natives called Kooderoo. He continued on up the coast, subsisting on what the Watharoung called Kooderoo, which we know as abalone, which was abundant in the area. He passed through the Karaaf River and the River that pass through modern day Torquay at the beginning of what is today the Great Ocean Road. Buckley was just travelling further into the wilderness.

Adding to Buckley’s suffering throughout this time was the fact that water was hard to come by. On top of this, when he ate the abalone it made him thirstier. He would have to rely on the dew that collected on the branches in order to survive.

If we look at the direction Buckley was travelling in at this point we will see that he was actually going in the opposite direction of Sydney, his supposed destination. Sometimes he would spot the abandoned huts of the natives. At others he would see wild dingoes and their howlings haunted him at night.

He continued travelling along the coastline in a South-Westerly direction passing through the areas of modern day Angelsea and Airey’s Inlet. Luckily he found the natives had been burning the bush here and managed to procure a firestick for himself. At this location he also found a native well, some berries in bushes and a great supply of shellfish which he was able to cook on his new fire. Buckley talks of giving up great thanks to God for this because he had been growing weak all the time due to the conditions he had been living under.

He continued on down the coast and two days later came to Mt. Defiance which the natives called Nooraki. Here he decided to settle down for a while as his body had begun to break out in strange sores, probably as a result from suffering from scurvy from malnutrition. He created a more permanent shelter and found some edible plants nearby that could sustain him and stayed in the area for a few months.

Eamonn Gunning 2017

Do you enjoy this content? Would you like to see more of it? Please help me reach my goal of publishing a book on Mr Cruel by making a one-time donation to help me cover the many costs I have incurred in carrying out this research. These costs have included subscription costs to a host of research tools and databases and costs associated with running this website and the associated podcast.

Make a one-time donation

Do you enjoy this content? Would you like to see more of it? Please help me reach my goal of publishing a book on Mr Cruel by making a monthly donation to help me cover the many costs I have incurred in carrying out this research. These costs have included subscription costs to a host of research tools and databases and costs associated with running this website and the associated podcast.

Make a monthly donation

Do you enjoy this content? Would you like to see more of it? Please help me reach my goal of publishing a book on Mr Cruel by making a yearly donation to help me cover the many costs I have incurred in carrying out this research. These costs have included subscription costs to a host of research tools and databases and costs associated with running this website and the associated podcast.

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is greatly appreciated appreciated.

Melbourne Marvels

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

Melbourne Marvels

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

Melbourne Marvels